Yaroslava's story is hardly different from many others on the eve of the full-scale war: anxiety, endless talk about an emergency "go-bag," news of Russian troops at the border, and alongside it all, ordinary life with its own small and large dramas. On the eve of the great war, Yaroslava was working as a communications officer for the "Slidstvo.Info" editorial office and finishing her Master's degree in journalism at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Before the war, as Russia massed its troops on the border, many media outlets began to prepare, including "Slidstvo." But at the time, the severed limbs discussed in training sessions and the heavy body armour seemed more like a scene from an American blockbuster than something that might genuinely be needed in the near future.

On the night of the 24th of February, Yaroslava was finishing homework that was due to be discussed with her entire group at the Mohyla School of Journalism the next day. She then went on a date, leaving some of her things at the office to pick up "tomorrow." For her, the war began with calls from her ex-boyfriend's parents at 5 a.m., the television blaring, and a knot in her stomach that made her want neither to eat nor drink.

Then came snippets of conversations on the street as she returned home that morning; an argument with her mother about that same ex-boyfriend; monks with suitcases leaving the Lavra; messages on people's screens in the metro about whether to go to work or not. And long queues of cars at petrol stations on the way out of the city, forcing her to walk for 40 minutes from the metro.

Returning to her flat in Borshchahivka, she immediately got back to work. At that moment, not yet fully comprehending what was happening, it provided at least some "anchor" to cling to. "You just keep working. On some kind of autopilot, you just keep going. You work, work, work. We were constantly publishing news; you're constantly monitoring this news."

Only late in the evening, in the darkness of her own flat, did she allow herself a moment of weakness. Late that evening, the windows trembled from explosions for the first time. "I broke down. I started crying. And then, literally a few minutes later, I opened the news and started working again. I cooked some noodles because I realised I was starting to feel ill, having eaten nothing since the morning." This was her formula for survival: acknowledge the pain, but not let it paralyse her.

The next day, her parents collected her and took her to their house just outside Kyiv. "They said: 'Listen, we're leaving, we'll pick you up... It will be safer'." Well, so we thought." Their house was located on the Zhytomyr highway, in the Bucha district, a few hundred metres from the village of Berezivka, a name that would soon be known to the entire world.

Packing her rucksack, she acted rationally, as if on a work trip. "I remember I packed my laptop, camera, phones, all the devices. I didn't pack a single bra, because I decided it was unnecessary weight." Among the warm clothes, her choice fell on an Oxford bomber jacket. "The funny thing was, it was an Oxford bomber jacket my mum had brought me a few years ago. I just took it because it had a zip. And it was warm."

A few days later, they found themselves under occupation. Life moved between the house and the cellar; on some nights, everything around them was on fire. "You have no idea if you'll get out of there alive or not. You can already hear them shooting at cars on the highway." In this situation, all decisions and further actions depended on a tactical assessment of the situation, which changed daily: if it was a sunny day and the batteries were charged, you could even have a shower, but quickly, because getting undressed during explosions is not something you want to do. While there was internet, she continued to work. When it was gone, she helped cook soup, which they then shared with the neighbours. And there was a lot of talking and moments of "freezing," just sitting in silence and waiting.

Among these was a conversation with her mother about a plan of action in case Russian soldiers entered the house. "She says: 'Well, Yaroslava, we need to talk. If they come in, you must be the first to escape'... I can't imagine being in my mum's shoes, having to say that to her own daughter."

"I wouldn't say I'm very brave in this context... you just continue to do what you can do."

Leaving the occupied area was a risk; staying was just as much of one. After all, it was February, there was no electricity in the village, and shells were constantly flying over the house. "You drive out onto the highway, their tank aims at your car. And you're just like: 'Well, this is it, then'." Yaroslava guesses that Ukrainian artillery, which distracted the enemy, saved them.

After this ordeal, she returned to work quite quickly, publishing and sharing the investigations her colleagues were producing. Work was a way to process and find meaning in the sheer chaos. It wasn't just a job; it was a way to comprehend and structure the chaos.

The next stage was moving to Brussels. It was a difficult decision. "I cried half the night. I didn't really want to leave, but my parents' house was still under occupation; the situation was very unclear." The contrast between her internal state and the peaceful European city was stark. "It was so strange to leave and see people who were calm."

In Brussels, Yaroslava was offered a job as a journalist—writing about agricultural policy and, at the same time, figuring out how the system of EU institutions works from the inside. That same summer, Ukraine was granted EU candidate status, and the issue of grain exports became acute, so there was plenty of work.

It was then that her mother sent her information about a scholarship at Oxford. Yaroslava initially dismissed the idea. "I opened it. I thought, this isn't for me. I closed it... it didn't even have what I'm interested in." Oxford wasn't even a dream; she planned to continue in journalism.

But one night, unable to sleep, she simply opened the document and started writing her application—not with an "Oxford has always been my dream" attitude, but honestly and very directly explaining who she was and what she wanted to do on the university's programme. She did it without any real hope, almost mechanically, just following the requirements from the website. "I did everything possible not to get in here," Yaroslava jokes.

The result shocked her. The letter of congratulations and the offer of a full scholarship seemed like a joke. "I remember just sitting there, staring. I thought, really? No, it can't be." It wasn't the triumph of a dreamer, but a glitch in her clear plans. The notification on her desktop was open next to an application for a permanent position in that same city of Brussels, and it meant moving to a third country in the last five months, with a completely different circle of people, culture, and way of life.

In Oxford, alongside studying a completely new subject, Yaroslava joined the Ukrainian society, eventually becoming its president. In 2023, the challenges and the situation had changed somewhat: "When we arrived, the enthusiasm had waned a little, so questions of long-term impact arose: creating Ukrainian studies [programmes], finding funding." They organised not just events, but strategic projects that built Ukraine's presence in the academic space.

Like many Ukrainian students at European universities, she had to engage in direct political struggle and a great deal of advocacy. "‘You are ambassadors for your country’," they were constantly told. "I believe this is part of my responsibility as a Ukrainian student who has the opportunity to be inside this system and do my research here. I am also well aware that I am alive and have this opportunity thanks to those who went to defend Ukraine in the trenches. But this also means much more pressure, workload, and effort than is often required from any other students from outside a war context, who can just get on with their programme (and Master's programmes at Oxford are considered among the most intensive of all)."

Securing funding for a PhD was the next challenge: Yaroslava had several offers to study, but they didn't include money. So, alongside this, she had to finish her academic paper, look for a job, and find housing. All in the space of two months.

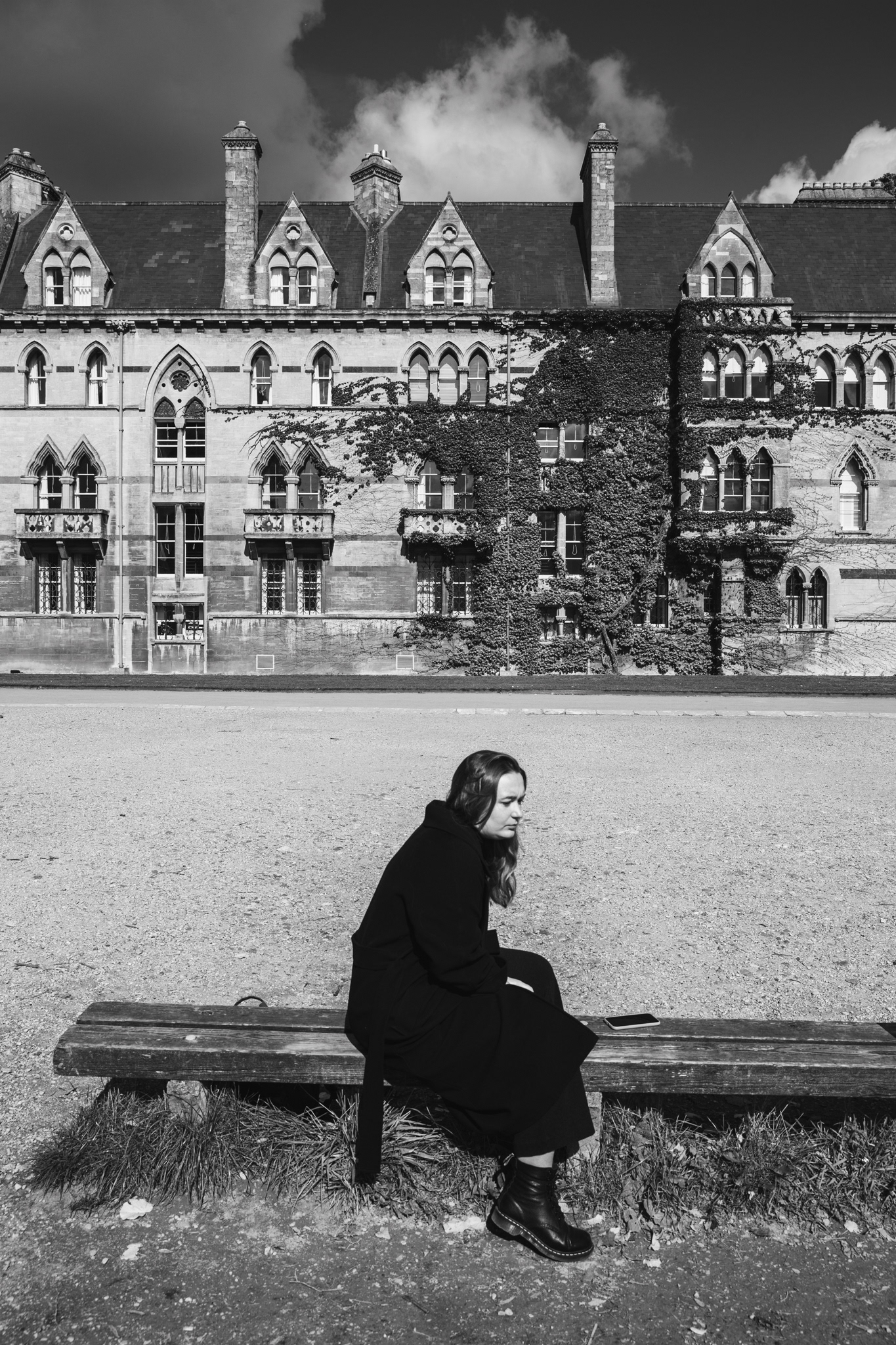

It was a moment of extreme pressure. "I still remember that moment when I just went to my college and lay down on the lawn. And I understood that in two weeks, I would be homeless and jobless." But instead of panic, she felt calm. "Apparently, a distinction from Oxford and five years of work experience weren't enough for a job in media and research. Plan 'B' was to go and work in the service industry—we often joked about this with friends who were in a very similar situation."

Just when the plan had become to move to London, work in a pub, and pay for part-time study at UCL herself, Yaroslava's college offered her a scholarship to study—two weeks before she was due to decline their offer.

Having received this opportunity, Yaroslava immersed herself in work that became a logical continuation of her path as a journalist and activist. Her doctoral research is not abstract theory, but an attempt to make sense of what she herself has experienced. "In general, I work with how knowledge about the war, and the war itself and its presence, cross borders. What even is 'proximity to war,' and how is this war, for example, represented here, abroad?"

The process of working on a PhD at Oxford turned out to be very independent, which suited her character perfectly. She doesn't wait for instructions but manages her own research. "I see my supervisors once a month, and our meetings are basically structured not so that they ask me things, but so that I ask them questions in the course of my work. I am the researcher; I am doing this research. Not them, it's not their responsibility."

Her method is anthropology. This means a deep immersion in the context through communication with people. "Anthropology, in principle, is collecting information by talking to people a lot... You try to understand how they see the world." She conducts online interviews, collaborates with podcasters, attends events—all to gather a multifaceted picture of how the war is perceived.

However, she works under strict limitations. The main one is the university's ban on conducting official fieldwork in Ukraine. "I cannot do research in Ukraine. Oxford doesn't allow it due to security risks—and not just for me; this is common practice here for academics working on Ukraine. Therefore, if I go to Ukraine, I do so as a 'private visit'; I am not officially allowed to do my research there, even though I am Ukrainian." This forces her to find creative methods for gathering information and once again highlights the chasm between her reality and the safe world of British academia.

The scale of the work is colossal: in a few years, she needs to write a 100,000-word dissertation. "That can mean up to 500 pages of academic literature to get through in a week... Writing 30-40,000 words in three months in English, when you are not a native speaker, is very hard."

For Yaroslava, this research has not only academic but also practical value. She does not want her work to be left on a library shelf. "I don't see the point in doing research if it doesn't convert into some real-world impact." An example of such impact is the panel discussion on supporting Ukrainian media that she organised in the British Parliament after USAID suspended its programme in Ukraine. This is her goal: to turn academic knowledge into real action.

When asked how she learned to adapt, Yaroslava answers honestly: "I didn't." She doesn't try to forget. She has integrated this experience into her identity. "I know the price of being here. I know that if it hadn't been for the Ukrainian artillery back then... we would never have left that village." This sense of responsibility has become her main motivator. "It would be simply foolish and irresponsible to waste this opportunity."

She works with a therapist but admits that she often talks not so much about the war as about ordinary life challenges. "These life things, all the stories, with childhood traumas and all that stuff, they don't just disappear." The war is part of her reality, but not her entire personality.

Life at Oxford has given her a broader perspective on the world and changed how she approaches her work and advocacy. "I really dislike that many Ukrainians here, for some reason, frame themselves from a perspective of, 'you owe us'... The point is that nobody owes anyone anything. The British do not owe Ukrainians, and it's important to understand that. Likewise, unfortunately, Ukraine is not the only country where there is a war."

She is convinced that the responsibility for promoting Ukraine's image lies with Ukrainians themselves. "It is not the responsibility of the British that they don't know enough about Ukraine. It is also Ukraine's responsibility, on many levels—including telling people about its own country."

She describes her journey to Oxford and her PhD work as a process that demands, above all, honesty with oneself. "You don't need to write, 'I want to come here because Oxford is the best place in the world.' Figure out why you need it. And be honest about whether you need it at all."

Her own philosophy boils down to a simple but powerful formula, one that explains her resilience better than any psychological theory: "Sit down and work hard. No, seriously, if I'm being completely honest. I just really don't know any other way... What do you do? You just keep working."

These are not just words. This is her method. A method that has allowed her to turn chaos into structure, tragedy into opportunity, and pain into strength. Yaroslava's story is not about luck or a miracle. It is about unshakeable will and the ability to keep working, no matter what.